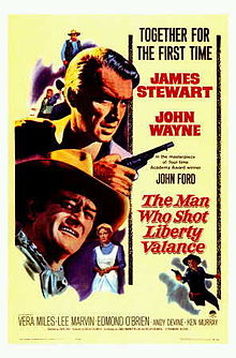

“This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” This oft quoted line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (Ford, 1962) epitomizes how Americans prefer romance over reality when it comes to the history of our expansion into the western territories. The notion of bringing eastern civilization to the vast wilderness of the West became inextricably entwined with our country’s obsession with Manifest Destiny, and one reason why the Western is considered the most “American” of genres, and why this taming of the West became part of the mythology of the American collective consciousness. (Pippin 62) To capture this obsession, cinematic storytelling needed a visual concept to match this monumental, overarching, Big-Sky of a narrative. But it wasn’t until director John Ford, and his now iconic visual design for Stagecoach (1939), that this concept coalesced into convention with one long sweeping shot of the camera; shot on location in Monument Valley, Utah, these vast vistas of the southwest soon became synonymous with the Western genre. Yet, twenty-three years later, in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Ford tackles the same theme of civilizing the West with a very different perspective from his 1939 film. Shot almost entirely on manmade sets on the sound stages of Paramount Studios, the 1962 release of Liberty Valance exemplifies the evolution of not only the auteurship of director John Ford, but the very genre itself as those iconic Old West vistas acquiesce to the confinement of interior views, and lawless wilderness gives way to cultivated civilization.

Gathering some historical background regarding the social, political and economic influences of the times, as well as what was going on in the film industry, serves to illuminate the evolution of some of the myths and conventions as we witness them through the lens of John Ford’s two most lauded Westerns. This examination exposes why this most American of genres grew strong and maintained that strength over a period of sixty years as the Western became synonymous with the expansion and evolution of America itself.

The trauma of the Great Depression and the ensuing economic, social and political fallout provides the backdrop against which Stagecoach emerged. In 1930, in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929, twenty-five percent of Americans were out of work. By 1932, Americans had had enough of President Hoover’s lack of action to alleviate their suffering, and elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt to lead this country back from the brink of destitution with his New Deal, creating a safety net for many desperate Americans. While still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, the plains states experienced the worst drought in American history. The Dust Bowl saw 2.5 million people abandon their farms and head west to California, looking for any kind of employment and hope for the future. (History.com) Spare change was a luxury, and “Brother, can you spare a dime?” was a sad lyrical testament of such. Alternately, popular Swing music (1935-1946) provided a more optimistic perspective, if only for the length of the song. Yet, while money was tight, people kept going to the movies. Further encouragement and reason to be hopeful came via FDR’s second New Deal in 1935, offering more aggressive work programs. Labor reform in the form of The National Labor Relations Act brought a more egalitarian work atmosphere, and with it, hope for a better life. (History.com) By decade’s end, Roosevelt’s programs had done their job getting many Americans back to work, but the threat of war loomed on the horizon like an impending wall of darkness. Americans more than ever needed an escape from these ongoing stresses and struggles, and longed for better times. What better peg to hang their hat-of-hope on than the most intrinsically American offering of the film industry, the Classic Hollywood Western?

Gathering some historical background regarding the social, political and economic influences of the times, as well as what was going on in the film industry, serves to illuminate the evolution of some of the myths and conventions as we witness them through the lens of John Ford’s two most lauded Westerns. This examination exposes why this most American of genres grew strong and maintained that strength over a period of sixty years as the Western became synonymous with the expansion and evolution of America itself.

The trauma of the Great Depression and the ensuing economic, social and political fallout provides the backdrop against which Stagecoach emerged. In 1930, in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929, twenty-five percent of Americans were out of work. By 1932, Americans had had enough of President Hoover’s lack of action to alleviate their suffering, and elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt to lead this country back from the brink of destitution with his New Deal, creating a safety net for many desperate Americans. While still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, the plains states experienced the worst drought in American history. The Dust Bowl saw 2.5 million people abandon their farms and head west to California, looking for any kind of employment and hope for the future. (History.com) Spare change was a luxury, and “Brother, can you spare a dime?” was a sad lyrical testament of such. Alternately, popular Swing music (1935-1946) provided a more optimistic perspective, if only for the length of the song. Yet, while money was tight, people kept going to the movies. Further encouragement and reason to be hopeful came via FDR’s second New Deal in 1935, offering more aggressive work programs. Labor reform in the form of The National Labor Relations Act brought a more egalitarian work atmosphere, and with it, hope for a better life. (History.com) By decade’s end, Roosevelt’s programs had done their job getting many Americans back to work, but the threat of war loomed on the horizon like an impending wall of darkness. Americans more than ever needed an escape from these ongoing stresses and struggles, and longed for better times. What better peg to hang their hat-of-hope on than the most intrinsically American offering of the film industry, the Classic Hollywood Western?

“There is no road, but there is a will, and history cuts the way.” (Simmon 105)

By 1939, the Western genre had already become firmly entrenched in our social psyche beginning in the mid-1800s with the Beadle books and dime novels of the day, the most popular of which were about the burgeoning West. (Smith 91) Americans couldn’t get enough of the stories about Buffalo Bill, aka ‘Wild Bill Cody,’ and various other cowboy heroes of the West. Their adventures and conquests, as well as their virtues, intrigued us. These western heroes were described as “generous, brave, and scrupulously honest, with ‘a strange, paradoxical code of personal honor, in vindication of which he will obtrude his life and though it were but a toy.’” (Smith 109) Through these books, these larger-than-life heroes gained a firm foothold with American readers, and the movies were a natural extension for this already established audience base.

In 1939, the American psyche, still reverberating from the blunt force trauma of economic disaster, stood poised at the box office with this hope in hand when John Ford commissioned Dudley Nichols to adapt Ernest Haycox’s short story, “The Stage to Lordsburg” into a screenplay. The groundwork had been laid for Stagecoach to thunder onto the screen with its archetypal heroes and villains intact. And God knows America needed heroes who knew right from wrong, and could save the day when saving was most crucial.

While the country regained its balance, the film industry stood stronger than ever. Industry specific elements influenced how films were made during this time, and include the mass production of films of the studio system itself, vertical integration, the Production Code, and the already firmly established Western genre. The mass production of movies ensured the studios had crews already on salary as well as have crews that specialized in specific genres. Vertical integration helped studios define what the audiences liked and didn’t like, and responded quickly to provide what the paying customer required. This in turn influenced what genres formed, and what formulaic elements stayed and those that didn’t, resulting in the myths, conventions and iconography that made it through the gauntlet of audience approval – those that made cents. Let us not forget the influence of the Production Code ensuring that villains got their comeuppance, and the archetypal hero flourished.

Perhaps because in 1939 we were still trying to tame the chaos that surrounded us, and the future seemed uncertain, we sought civility and continuity in our lives, and felt nostalgic for a time when we could tell the bad guy from the good: all this coalesced at once in Stagecoach.

In the mid- to late-1800s, a vast portion of the continent lay as open territory before us; one whose shores needed to shake hands via the transcontinental railroad. (“East coast, meet West coast.” “My pleasure, I’m sure.”) The age of enlightenment was well established; industrialization well underway; and the Native Americans (translated in the vernacular of the day as Indians or savages) needed spiritual enlightenment (or so was purported), or at the very least in need of the lightening of their burden of land stewardship, with which most were more than happy to help. Ahead lay the wilderness, the great unknown, and the dangers that lurk in the darkness (spiritual as well and physical). In Stagecoach, the impending attack by the Apache Indians became the perfect foil against which our eclectic ensemble of adventurers and brave cavalry must fight for their lives. (Budd 590) Thus, by personalizing the fight to include Ford’s socially stratified cast of characters that we’ve come to care about, the classic chase sequence and battle between these civilized folk (that we know) and the savage Indians (representing “a threat” more than real people), becomes part of both myth and convention of the Western genre. In the classical tradition, the goals and intentions of the good guys and bad guys are clearly defined, and we know who to root for. This clear definition of values (the good guys wear white hats, the bad guys wear black, or war paint) is one of the conventions of the classic Western. No ambiguity here.

Among the genre defining decisions that John Ford made in the making of Stagecoach, one of the most significant for this film and for the genre was his decision to shoot on location in Monument Valley, not far from the Arizona-Utah border. The wide-angle shots and deep focus Ford used to film in Monument Valley – considered as one of the top ten iconic movie locations (Crapanzano 2010) – helped establish Ford’s personal style of Western, and eventually became associated with Westerns in general, serving as both convention and iconography.

By 1939, the Western genre had already become firmly entrenched in our social psyche beginning in the mid-1800s with the Beadle books and dime novels of the day, the most popular of which were about the burgeoning West. (Smith 91) Americans couldn’t get enough of the stories about Buffalo Bill, aka ‘Wild Bill Cody,’ and various other cowboy heroes of the West. Their adventures and conquests, as well as their virtues, intrigued us. These western heroes were described as “generous, brave, and scrupulously honest, with ‘a strange, paradoxical code of personal honor, in vindication of which he will obtrude his life and though it were but a toy.’” (Smith 109) Through these books, these larger-than-life heroes gained a firm foothold with American readers, and the movies were a natural extension for this already established audience base.

In 1939, the American psyche, still reverberating from the blunt force trauma of economic disaster, stood poised at the box office with this hope in hand when John Ford commissioned Dudley Nichols to adapt Ernest Haycox’s short story, “The Stage to Lordsburg” into a screenplay. The groundwork had been laid for Stagecoach to thunder onto the screen with its archetypal heroes and villains intact. And God knows America needed heroes who knew right from wrong, and could save the day when saving was most crucial.

While the country regained its balance, the film industry stood stronger than ever. Industry specific elements influenced how films were made during this time, and include the mass production of films of the studio system itself, vertical integration, the Production Code, and the already firmly established Western genre. The mass production of movies ensured the studios had crews already on salary as well as have crews that specialized in specific genres. Vertical integration helped studios define what the audiences liked and didn’t like, and responded quickly to provide what the paying customer required. This in turn influenced what genres formed, and what formulaic elements stayed and those that didn’t, resulting in the myths, conventions and iconography that made it through the gauntlet of audience approval – those that made cents. Let us not forget the influence of the Production Code ensuring that villains got their comeuppance, and the archetypal hero flourished.

Perhaps because in 1939 we were still trying to tame the chaos that surrounded us, and the future seemed uncertain, we sought civility and continuity in our lives, and felt nostalgic for a time when we could tell the bad guy from the good: all this coalesced at once in Stagecoach.

In the mid- to late-1800s, a vast portion of the continent lay as open territory before us; one whose shores needed to shake hands via the transcontinental railroad. (“East coast, meet West coast.” “My pleasure, I’m sure.”) The age of enlightenment was well established; industrialization well underway; and the Native Americans (translated in the vernacular of the day as Indians or savages) needed spiritual enlightenment (or so was purported), or at the very least in need of the lightening of their burden of land stewardship, with which most were more than happy to help. Ahead lay the wilderness, the great unknown, and the dangers that lurk in the darkness (spiritual as well and physical). In Stagecoach, the impending attack by the Apache Indians became the perfect foil against which our eclectic ensemble of adventurers and brave cavalry must fight for their lives. (Budd 590) Thus, by personalizing the fight to include Ford’s socially stratified cast of characters that we’ve come to care about, the classic chase sequence and battle between these civilized folk (that we know) and the savage Indians (representing “a threat” more than real people), becomes part of both myth and convention of the Western genre. In the classical tradition, the goals and intentions of the good guys and bad guys are clearly defined, and we know who to root for. This clear definition of values (the good guys wear white hats, the bad guys wear black, or war paint) is one of the conventions of the classic Western. No ambiguity here.

Among the genre defining decisions that John Ford made in the making of Stagecoach, one of the most significant for this film and for the genre was his decision to shoot on location in Monument Valley, not far from the Arizona-Utah border. The wide-angle shots and deep focus Ford used to film in Monument Valley – considered as one of the top ten iconic movie locations (Crapanzano 2010) – helped establish Ford’s personal style of Western, and eventually became associated with Westerns in general, serving as both convention and iconography.

Stagecoach illustrates well both the era and genre by use of the classic narrative form of storytelling, with a clearly defined beginning, middle and end, and its adept use of continuity editing. (Simmon 103) Along with this classic narrative form, the story utilizes simple, archetypal characters: reformed gunslinger, harlot with a heart of gold, the lady, the gambler, the corrupt banker, the town drunk. As if they were wearing masks of Comedia dell’arte, we feel secure in our recognition of each type – no surprises here.

However, its security that doesn’t last. As we move forward twenty-three years to 1962, we encounter a very different reality from that of 1939. The world now knows the apocalyptic power of the atomic bomb. World War II no longer loomed; it had torn countries, families, and the world apart. Allies were now enemies. The cold war chill coupled with the threat of nuclear war continues for decades. The 1950s and early 60s brought us the Interstate Highway Act (supporting American’s love for their cars and the freedom to use them), the space race with the Soviet Union (initiated by their launch of Sputnik), McCarthyism (Hollywood Blacklisting caused mistrust among colleagues), the birth of Rock and Roll, the Civil Rights Act, electing John F Kennedy, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. All of which informed us about the tentative and delicate balance of the world we now lived in. Alaska and Hawaii made it an even fifty in 1959, and two years later, NBC began broadcasting Hollywood films on TV with its “Saturday Night at the Movies.” Television had come home to roost, and the film industry took a major hit financially. Modernist film was on the rise under the influence of the French New Wave cinema, and its penchant for stirring up the pot by examining social and political issues, and blending genre and character lines. The perfect recipe for director Ford to “stand and deliver” his next Western masterpiece.

Departing from this depot of mid-century misgivings and mistrust, we arrive in Shinbone with Jimmy Steward and Vera Miles aboard a locomotive, suggesting that times have changed. They arrive not across an open expanse of the wild west, but around a bend with a terraced hill as backdrop. Gone are the sweeping vistas and wide-open spaces of Ford’s Monument Valley. Almost the entire film was shot on sound stages of Paramount Studios: controlled and confined interior spaces reflecting our societal need to control our environment. As a matter of fact, we rarely glimpse the sky in any of the sequences shot in the old Shinbone. Now juxtapose the vistas with air of confinement, and you have another example of how conventions in the Western genre evolved over time. (Place 216) The question one asks is why? Why did Ford change his M.O. just for this one?

Even though many now consider John Ford an auteur of incredible depth, breadth and style, unmatched in the Western genre, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance did not find its production home easily. By the early 1960s, Westerns were losing ground in the feature film department to “more relevant,” less sentimental, nostalgic styles; Ford tended toward both sentiment and nostalgia in his Westerns. The studio system, under which Ford flourished, was all but defunct after the Paramount antitrust decision of 1948, and he had to shop his picture among several studios, all of which turned him down. He finally found funding and support through an independent producer, but had to shoot with a much smaller budget than originally planned. Was this lack of funds why he created the world of Liberty Valance on sound stages (budget conscious) instead of shooting on location (more expensive)? Regardless of the rumors as to why, he shot in black and white rather than color, and it does lend to the overall nostalgia of the “story within the story” narrative.

Compared to the archetypal personalities of Stagecoach, we see an evolution into sophisticated complexities of character and narrative in Valance, where we have two equally likeable, but not perfect, protagonists competing for the love interest. Protagonist 1: Tom Doniphon - (John Wayne) a slightly reformed, self-centric, homesteading gunslinger (how’s that for complexity?) who ends up doing the unselfish thing by shooting Liberty Valance to save the competing protagonist life, and loses the girl in the process. Protagonist 2: Ranse Stoddard – (James Stewart) a slightly egotistical, but well-meaning east coast lawyer who believes he can single handedly bring civilization to the wilderness of Shinbone by bravely, if ineptly, standing up to villain Valance in a gunfight. He has the law on his side, but he will die in a fair fight with Valance. Tom is the better gun, and he would rather handle things the old-fashioned code-of-the-West way, with gun slinging skill. Yet, Tom’s ways must fade away if we are to have civilization, law and order. (Pippin 98) It is unclear which of the two we should root for. Ambiguity prevails. Not only do characterizations become shades of gray rather than black and white, so does the social and political subtext as to what price progress. We stare our dream of manifest destiny right in the kisser; its beauty faded, and we are forced to see its flaws.

Stagecoach leaves us with it’s sweet, tied-up-with-a-bow ending where Ringo Kid, protagonist-hero-ex-gunslinger, gets freedom and the girl. Liberty Valance leaves a bitter taste in the mouth, as Ford blends nostalgia and loss right into the closing scene as Mrs. Stoddard stares blankly out the train window at the end of the movie. “Aren’t you proud?” she asks Ranse, and we wonder if she means that his whole political career was built on a lie. We wonder if she means that Shinbone looks like a sterile facsimile of itself, no longer textured and breathing as it seemed to be throughout the long flashback scenes.

What we know is that as America evolves, so does our vision of that part of our history as exemplified in the Western genre. The Western is part of the American legacy, part of our narrative as a country, culture and people, and it will continue to evolve even as we do; we have a symbiotic relationship that way.

Works Cited

Budd, Michael N. A Critical Analysis of Western Films Directed by John Ford from Stagecoach to Cheyenne Autumn. 1975.

Cameron, Ian Alexander, and Douglas. Pye. The Book of Westerns. New York, Continuum, 1996.

Crapanzano, Christina. “Top 10 Iconic Movie Locations.” Time, Time, 17 May 2010, entertainment.time.com/2010/05/18/field-of-dreams-for-sale-top-10-iconic-movie-locations/slide/monument-valley-stagecoach/.

History.com Staff. “The 1930s.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2010, www.history.com/topics/1930s.

O'Connor, John E., and Peter C. Rollins. Hollywood's West: the American Frontier in Film, Television, and History. Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

Pippin, Robert B. Hollywood Westerns and American Myth The Importance of Howard Hawks and John Ford for Political Philosophy. Yale University Press, 2010.

Place, Janey Ann. The Western Films of John Ford. 1st ed., Secaucus, N.J., Citadel Press, 1974.

Simmon, Scott. The Invention of the Western Film: a Cultural History of the Genre's First Half-Century. Cambridge; New York, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Smith, Henry Nash., and American Council of Learned Societies. Virgin Land; the American West as Symbol and Myth. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1971.

However, its security that doesn’t last. As we move forward twenty-three years to 1962, we encounter a very different reality from that of 1939. The world now knows the apocalyptic power of the atomic bomb. World War II no longer loomed; it had torn countries, families, and the world apart. Allies were now enemies. The cold war chill coupled with the threat of nuclear war continues for decades. The 1950s and early 60s brought us the Interstate Highway Act (supporting American’s love for their cars and the freedom to use them), the space race with the Soviet Union (initiated by their launch of Sputnik), McCarthyism (Hollywood Blacklisting caused mistrust among colleagues), the birth of Rock and Roll, the Civil Rights Act, electing John F Kennedy, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. All of which informed us about the tentative and delicate balance of the world we now lived in. Alaska and Hawaii made it an even fifty in 1959, and two years later, NBC began broadcasting Hollywood films on TV with its “Saturday Night at the Movies.” Television had come home to roost, and the film industry took a major hit financially. Modernist film was on the rise under the influence of the French New Wave cinema, and its penchant for stirring up the pot by examining social and political issues, and blending genre and character lines. The perfect recipe for director Ford to “stand and deliver” his next Western masterpiece.

Departing from this depot of mid-century misgivings and mistrust, we arrive in Shinbone with Jimmy Steward and Vera Miles aboard a locomotive, suggesting that times have changed. They arrive not across an open expanse of the wild west, but around a bend with a terraced hill as backdrop. Gone are the sweeping vistas and wide-open spaces of Ford’s Monument Valley. Almost the entire film was shot on sound stages of Paramount Studios: controlled and confined interior spaces reflecting our societal need to control our environment. As a matter of fact, we rarely glimpse the sky in any of the sequences shot in the old Shinbone. Now juxtapose the vistas with air of confinement, and you have another example of how conventions in the Western genre evolved over time. (Place 216) The question one asks is why? Why did Ford change his M.O. just for this one?

Even though many now consider John Ford an auteur of incredible depth, breadth and style, unmatched in the Western genre, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance did not find its production home easily. By the early 1960s, Westerns were losing ground in the feature film department to “more relevant,” less sentimental, nostalgic styles; Ford tended toward both sentiment and nostalgia in his Westerns. The studio system, under which Ford flourished, was all but defunct after the Paramount antitrust decision of 1948, and he had to shop his picture among several studios, all of which turned him down. He finally found funding and support through an independent producer, but had to shoot with a much smaller budget than originally planned. Was this lack of funds why he created the world of Liberty Valance on sound stages (budget conscious) instead of shooting on location (more expensive)? Regardless of the rumors as to why, he shot in black and white rather than color, and it does lend to the overall nostalgia of the “story within the story” narrative.

Compared to the archetypal personalities of Stagecoach, we see an evolution into sophisticated complexities of character and narrative in Valance, where we have two equally likeable, but not perfect, protagonists competing for the love interest. Protagonist 1: Tom Doniphon - (John Wayne) a slightly reformed, self-centric, homesteading gunslinger (how’s that for complexity?) who ends up doing the unselfish thing by shooting Liberty Valance to save the competing protagonist life, and loses the girl in the process. Protagonist 2: Ranse Stoddard – (James Stewart) a slightly egotistical, but well-meaning east coast lawyer who believes he can single handedly bring civilization to the wilderness of Shinbone by bravely, if ineptly, standing up to villain Valance in a gunfight. He has the law on his side, but he will die in a fair fight with Valance. Tom is the better gun, and he would rather handle things the old-fashioned code-of-the-West way, with gun slinging skill. Yet, Tom’s ways must fade away if we are to have civilization, law and order. (Pippin 98) It is unclear which of the two we should root for. Ambiguity prevails. Not only do characterizations become shades of gray rather than black and white, so does the social and political subtext as to what price progress. We stare our dream of manifest destiny right in the kisser; its beauty faded, and we are forced to see its flaws.

Stagecoach leaves us with it’s sweet, tied-up-with-a-bow ending where Ringo Kid, protagonist-hero-ex-gunslinger, gets freedom and the girl. Liberty Valance leaves a bitter taste in the mouth, as Ford blends nostalgia and loss right into the closing scene as Mrs. Stoddard stares blankly out the train window at the end of the movie. “Aren’t you proud?” she asks Ranse, and we wonder if she means that his whole political career was built on a lie. We wonder if she means that Shinbone looks like a sterile facsimile of itself, no longer textured and breathing as it seemed to be throughout the long flashback scenes.

What we know is that as America evolves, so does our vision of that part of our history as exemplified in the Western genre. The Western is part of the American legacy, part of our narrative as a country, culture and people, and it will continue to evolve even as we do; we have a symbiotic relationship that way.

Works Cited

Budd, Michael N. A Critical Analysis of Western Films Directed by John Ford from Stagecoach to Cheyenne Autumn. 1975.

Cameron, Ian Alexander, and Douglas. Pye. The Book of Westerns. New York, Continuum, 1996.

Crapanzano, Christina. “Top 10 Iconic Movie Locations.” Time, Time, 17 May 2010, entertainment.time.com/2010/05/18/field-of-dreams-for-sale-top-10-iconic-movie-locations/slide/monument-valley-stagecoach/.

History.com Staff. “The 1930s.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2010, www.history.com/topics/1930s.

O'Connor, John E., and Peter C. Rollins. Hollywood's West: the American Frontier in Film, Television, and History. Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

Pippin, Robert B. Hollywood Westerns and American Myth The Importance of Howard Hawks and John Ford for Political Philosophy. Yale University Press, 2010.

Place, Janey Ann. The Western Films of John Ford. 1st ed., Secaucus, N.J., Citadel Press, 1974.

Simmon, Scott. The Invention of the Western Film: a Cultural History of the Genre's First Half-Century. Cambridge; New York, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Smith, Henry Nash., and American Council of Learned Societies. Virgin Land; the American West as Symbol and Myth. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1971.

© 2018-2020 by Colleen Dunn Saftler all rights reserved